by Otilia Dogaru

From an object of worship to a frontier of scientific ambition, the Moon has long occupied a central place in humanity’s imagination. It has inspired mythologies, guided agricultural cycles, and now serves as a platform for cutting-edge research and future exploration.

Since the earliest days of civilisation, the Moon has held profound symbolic and practical significance. Ancient cultures, such as Egyptian, Greek, Babylonian and Chinese revered it as a deity, timekeeper and celestial guardian. Mythological figures, like Selene and Chang’e, mirrored our attempts to make sense of the Moon and our connection to it and the turning point came with the dawn of telescopic astronomy.

Since the earliest days of civilisation, the Moon has held profound symbolic and practical significance. Ancient cultures, such as Egyptian, Greek, Babylonian and Chinese revered it as a deity, timekeeper and celestial guardian. Mythological figures, like Selene and Chang’e, mirrored our attempts to make sense of the Moon and our connection to it and the turning point came with the dawn of telescopic astronomy.

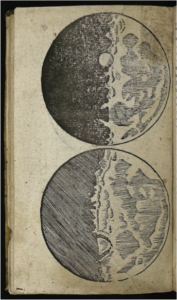

In 1609, Galileo Galilei’s observations of the Moon revealed craters and rugged terrain, challenging long-held beliefs of a flawless heavenly sphere. The Moon was no-longer a divine symbol, but a tangible world – one that could be studied, mapped and ultimately reached. Astronomers such as Johannes Hevelius and Michel van Langren expanded on Galileo’s work, creating some of the first lunar maps and laying the groundwork for modern selenography.

This growing body of knowledge set the stage for the 20th century, when the Moon became a geopolitical prize. During the Cold War, the Space Race turned the Moon into a symbol of technological supremacy. On 20 July 1969, that rivalry culminated in the Apollo 11 landing, when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to walk on its surface. The Moon was no longer out of reach.

Subsequent missions, such as Apollo 17, deepened our understanding of lunar geology and spaceflight capabilities and, more recently, unmanned missions by NASA, ESA, China and India have continued to explore the Moon’s surface and environment, contributing valuable data for future missions.

Today, the Moon is once again a focal point; NASA’s Artemis programme aims to return astronauts to the Moon later this decade (currently this is planned for 2027), with a specific focus on the south polar region.

Artemis III will not only land humans on the surface, but also deploy vital technologies to support long-term habitation, enabling the use of our Moon as a proving ground for deep-space exploration, which is crucial to our ambitions for Mars and beyond.

The British Interplanetary Society (BIS) has long envisioned this future. As early as the 1930s, the Society designed a lunar spacecraft capable of carrying a three-person crew, decades ahead of its time. In the following years, the BIS publications proposed detailed concepts for lunar habitats, pressure suits and mission architectures that echo many ideas now being considered by today’s space agencies.

The British Interplanetary Society (BIS) has long envisioned this future. As early as the 1930s, the Society designed a lunar spacecraft capable of carrying a three-person crew, decades ahead of its time. In the following years, the BIS publications proposed detailed concepts for lunar habitats, pressure suits and mission architectures that echo many ideas now being considered by today’s space agencies.

The BIS continues to contribute to the future of lunar science through its thought leadership and technical research. From concepts for far-side lunar radio telescopes to studies on inflatable bases and autonomous robotic construction, the BIS is helping shape a sustainable and cooperative future on the Moon. This commitment was also highlighted most recently in the Beyond the Moon Symposium, held during the 2024 Reinventing Space Conference. The event brought together scientists, engineers and policymakers to explore issues such as lunar governance, surface infrastructure and the ethical use of extraterrestrial resources, and more recently (as part of the Aqualunar Challenge) supported the development of Ganymede’s Chalice: A solar concentrator that turns lunar ice into drinkable water.

As we celebrate Moon Day, we are reminded of how far we have come and how far we still aim to go. The Moon, once a mystery, is now a beacon of human curiosity, of global cooperation, and of our shared desire to explore.

Marking this day is more than a look back. It is a call to keep pushing forward guided by science, driven by ambition and united by a vision that reaches beyond Earth.

Happy Moon Day!