by Mark Stewart, FBIS and Richard Hayes, FBIS

Editorial Team

Odyssey – the Science Fiction, Space Art and Cultural Magazine of the British Interplanetary Society

To the Moon and back – in a BIS spaceship

“Goonhilly: this is Tranquillity Base here: the Newton has landed.”

“Copy that, Newton. The team are about to turn blue here; we’re breathing again now.”

Despite what the conspiracy theorists think, it’s a well-documented fact, a matter of historical record, that America was the first nation to land astronauts on the Moon back in July of 1969 (unless of course you believe the account recorded in 1901 by a certain Herbert George Wells documenting his encounter with Selenites). But a case can be made for saying that the BIS got there first decades earlier, if only by means of the technical specifications it outlined for its own Moonship.

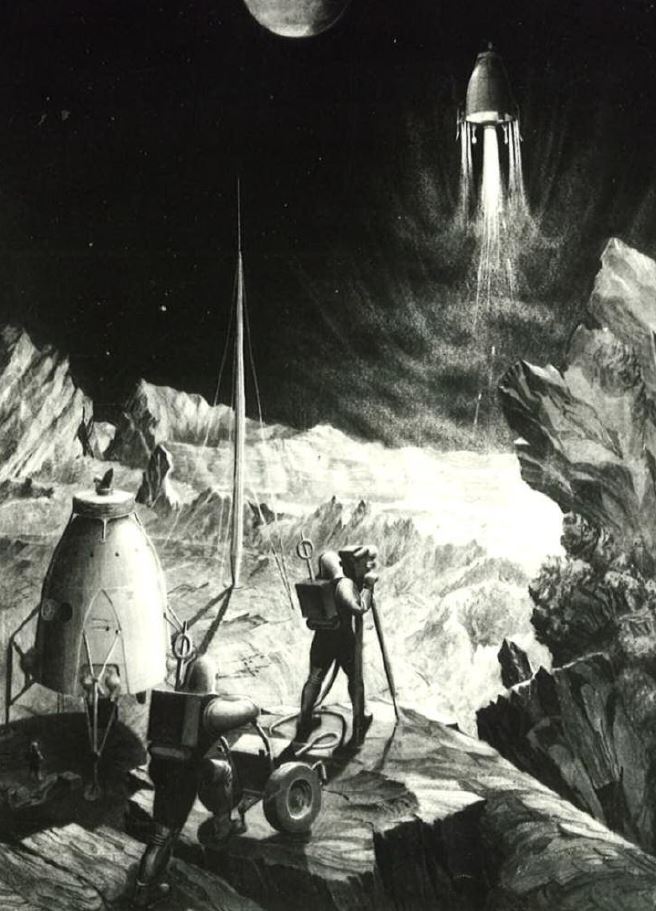

The Moon has long been a source of fascination for the BIS. Helping to reach the Moon through the advocacy of human spaceflight was one of the Society’s earliest goals, an ambition which attracted the submission of numerous papers to JBIS and frequent articles and letters to SpaceFlight. Treading the lunar regolith remains an abiding dream. Our satellite is a siren world, luring explorers to its surface regardless of the dangers and challenges of getting there. Since the advent of speculative fiction the Moon has become a crowded place, both above and below ground. The various spacecraft (real and imaginary) which rest upon its unchanging surface include a polyhedral “sphere,” a two man diving bell designed to fly through space powered by a strange substance – an anti-gravity metal – known as “Cavorite.” The footprints made by twelve astronauts on the lunar surface prove that this goal can be reached in fact as well as fiction. But there are other footprints “up there” too, such as those left behind by the sturdy walking boots of Professor Cavor in H.G. Wells’s classic tale, The First Men in the Moon. There can be little doubt that this eccentric but visionary physicist would have joined the BIS had it existed in turn-of-the century Britain. In fact, I can think of several current members of the BIS who resemble the professor very closely!

One of the main reasons for writing this article is to unlock some of the secrets contained in the BIS archive, especially for those members of the Society who can’t easily visit South Lambeth Road. There are no “Selenites” in the archive (more’s the pity, perhaps) but there are plenty of rare and fascinating items of major historical interest. This, then, is a route into those archives, a chance to explore the Society’s rich heritage.

* * *

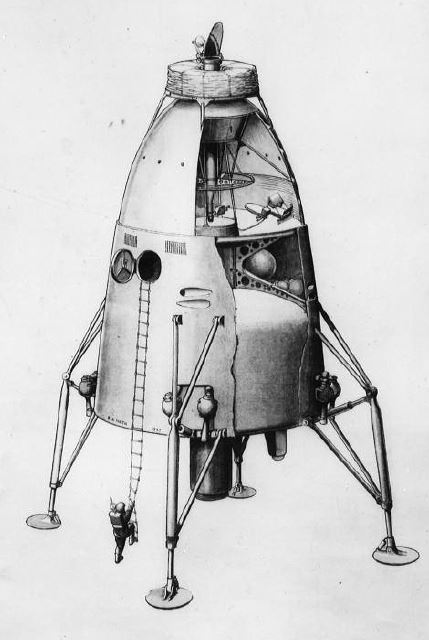

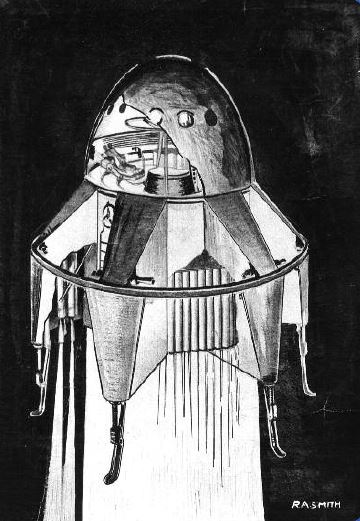

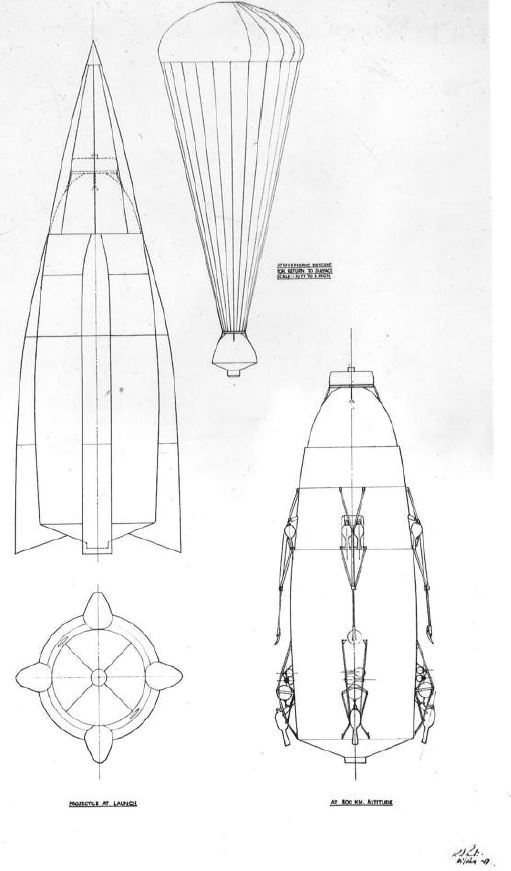

The late, great, and much missed Angela Carter (1940-1992) wrote many fine novels, amongst them The Magic Toyshop. Few writers have produced better novels so early in their writing careers, and The Magic Toyshop has one of the finest last lines in any novel: “At night, in the garden, they faced each other in a wild surmise.” I have always thought of the BIS archive as an enchanted place in its own right, a collection of rare treats. Amongst its many treasures are the paintings of R. A. Smith. The BIS Moonship – originally designed by the hugely talented Smith between 1937 and 1939 – represents a wide surmise unique to the BIS; a “What If” that still challenges the imagination today, over eighty years since Smith penned his wonderful designs:

- What if the Blue Streak and Black Arrow rocket programmes hadn’t been abandoned, along with the test range at Woomera in the wilds of the antipodean outback, a site which hosted the launch of many Anglo-Australian experimental rockets?

- What if the British government had ploughed the money that went into Polaris and Trident into ramping up the Blue Streak engines designed by Val Cleaver, resulting in a more muscular design capable of putting a British Saturn V into orbit, along with a Moon-bound crew?

- And what if at least one person in that crew had been a member of the BIS, determined to discover a fragment of Isaac Newton’s “great ocean of truth” which lies beyond the Earth’s thin atmosphere?

There is something distinctly “Wellsian” about the design of Ralph Smith’s Moonship. Indeed, it’s the sort of device that the hero of H.G. Wells’s most famous story might have constructed, had he not been so preoccupied in building a time machine. Perhaps Smith drew on the rich heritage of contemporary, or near contemporary, writers who shared a common dream – a desire to leave footprints on the surface of our nearest celestial neighbour. Given that John Beynon, better known as John Wyndham (author of The Midwich Cuckoos, The Day of the Triffids and The Kraken Awakes, amongst others), was a member of the early BIS, it is perhaps not such a stretch to extend that lineage just a little further back to the days of Wells himself. Had the ever dapper H.G. been a member of an Edwardian era BIS, the rocket ship that carried Bedford and Cavor to the lunar surface in The First Men in the Moon might well have displayed the BIS logo. The hesitant Cavor was – is – the archetypal English space explorer: an eccentric but gifted dreamer, equipped for a journey offworld with little more than a stout pair of walking boots and a tweed jacket. Imagine a BIS evening lecture with Professor Cavor as the speaker: Amongst the Selenites – My Time on the Moon. The BISH/Q couldn’t hold the crowd such a lecture would draw. If the multiverse theory is true, then perhaps in some other universe Ralph Smith’s design did in fact beat the Americans to the Moon. And maybe, in that other universe, BIS astronauts are even now descending the side of their lander, while the people of Earth look on, waiting and listening for confirmation of the landing: “That’s one small step for a man; one giant leap for the BIS.” Who knows? It might still happen. If we can set about designing starships – and Daedalus shows that we can indeed do just that – building a Moonship should be easy. I think Arthur C. Clarke would have loved the idea. And the challenge.